As the author of two of the most revolutionary, bestselling books about pregnancy and motherhood of the last decade, writer and speaker Angela Garbes is a formidable expert on the art of mothering. Her description of mothering as “sensual” and “endemic to the body” takes into account the history of mothering and care work as naturally female, and as a result, invisible and undervalued. This primal labor has historically also been considered the exclusive domain of women and of biological mothers. But recent shifts in consciousness are investigating how mothering and parenting can include more shared duties, less restrictive definitions, and a more complex understanding of what (and who) a mother is.

Some believe that babies choose their mothers, while others may take on the care work of mothering by chance or circumstance. Remember, you can choose to be a mother (or not to be!) in your own time, and there is no one right path to motherhood. To help us explore a more expansive, inclusive definition of mothering, here’s an overview of five surprising ways to mother that don’t include giving birth.

Have you heard of the mother wound? Family practitioner Dr. Oscar Serrallach describes this matrilineal burden as “the pain and grief that grows in a woman as she tries to explore and understand her power and potential in a society that doesn’t make room for either, forcing her to internalize the dysfunctional coping mechanisms learned by previous generations of women.” Psychologists sometimes consider the mother wound as part of a complex intergenerational cycle of trauma inherited from one generation to the next. On the flip side, many have argued that tending to the “mother wound” (though not an official mental health diagnosis) can lead us to profound healing. Psychologist Nadine Macaluso attributes the effects of the mother wound to “the cultural atmosphere of female oppression by the Western patriarchy”, under which conditions women constantly question their worth and their belief systems, developing trauma coping mechanisms that are passed down to their own daughters. While much of the discussion around mother wounds is centered on grandmothers, mothers and daughters (the female ancestral lineage), there’s also a lot of evidence that sons may experience this type of injury to the psyche in the absence of a strong bond with their mothers, or due to a fraught relationship with their maternal figures.

The harsh reality is that few of us come into adulthood unscathed, whether our wounds stem from the mothers of our lives or other deep-rooted childhood pain. With this in mind, we would be wise to work in harmony with our trusted professionals (therapists, healers, herbalists, somatics practitioners, etc.), our loving family and friends, to seek out ways to offer our inner child the healing they deserve. Just as there is no one right path to motherhood, there is no one-size-fits-all cure for healing childhood wounds. We applaud all of you who are doing the messy and painful work of (re)mothering your inner child.

When children become “parentified”, experts say it can have a lifelong impact, often resulting in compulsive caretaking behaviors as they come into adulthood. If you were responsible for your parents or siblings as a kid, it may have been due to loss, addiction, illness, deportation, incarceration, or a myriad of other circumstances. Whatever the reason for this dynamic role reversal, Lost Childhoods author Gregory Jurkovic writes: “Children’s distrust of their interpersonal world is one of the most destructive consequences of such a process.” During the most formative years when our attachments and bonds are either fortified or broken in some way, we may have been forced to learn how to mother (regardless of our gender) prematurely to protect and raise other family members who were unable to mother themselves.

When children become “parentified”, experts say it can have a lifelong impact, often resulting in compulsive caretaking behaviors as they come into adulthood. If you were responsible for your parents or siblings as a kid, it may have been due to loss, addiction, illness, deportation, incarceration, or a myriad of other circumstances. Whatever the reason for this dynamic role reversal, Lost Childhoods author Gregory Jurkovic writes: “Children’s distrust of their interpersonal world is one of the most destructive consequences of such a process.” During the most formative years when our attachments and bonds are either fortified or broken in some way, we may have been forced to learn how to mother (regardless of our gender) prematurely to protect and raise other family members who were unable to mother themselves.

In these situations, it’s often difficult to break the cycle of feeling vitally “needed” later in life, and this comes with both positive and negative outcomes, says child clinical psychologist Vicki Panaccione. “I think that [children who become “parentified”] are so self-sufficient and feel like they need to be in control and can’t ask for help,” Panaccione shared in an interview on NPR, “that it may be hard to let someone else in.” We acknowledge all those who have mothered siblings, parents, or other family members as essential to the health and wholeness of those they cared for, loved, and helped to grow along the way.

So pronounced is the burden on women and the myth of “maternal thinking” when it comes to protecting our ecosystems that some have argued that environmentalism has a gender problem. If everyone valued the potential and purpose of feminine power equally, we could possibly not only reverse the negative stereotypes of care work (whether for people, plants, animals, or the planet) as being relegated to women’s labor. Stewarding our earth mother requires a collective effort, though historically “activists involved in environmental advocacy are often mothers and many women within environmental justice serve as mothers to movements” (Source: Environmental Activism and the Maternal).

So pronounced is the burden on women and the myth of “maternal thinking” when it comes to protecting our ecosystems that some have argued that environmentalism has a gender problem. If everyone valued the potential and purpose of feminine power equally, we could possibly not only reverse the negative stereotypes of care work (whether for people, plants, animals, or the planet) as being relegated to women’s labor. Stewarding our earth mother requires a collective effort, though historically “activists involved in environmental advocacy are often mothers and many women within environmental justice serve as mothers to movements” (Source: Environmental Activism and the Maternal).

Mothering, as many are now reframing the concept, can be a way to feel, to imagine, and to act with the wellbeing of all generations—our ancestors, our living kin, and the world’s future children—at the forefront of our thinking. We honor and thank the mothers of the land, all caretakers of the living world, who together make up a network of hometown heroes. Our ecosystems need these mothers to be sustained.

A deep bow of gratitude goes out to the teachers, the nurses, the home caregivers, and countless other care workers who mother the most vulnerable members of our society. Often underpaid and overworked, these generous souls labor tirelessly on behalf of those who are in need of some form of mothering—to be bathed, to be held, to be talked and read to, to be fed, and so much more. And as one recent report from the Center for American Progress notes, “working mothers are important drivers of three essential industries—elementary and secondary education, hospitals, and food services—yet cannot afford child care for their own children.” This harsh juxtaposition of American caregivers and their own families’ unmet needs is yet another reminder of the important conversations we need to be having to ensure that all types of mothering is valued the way it deserves to be, for the sake of everyone’s future prosperity.

“Each family is unique,” writes speaker and caregiver supporter Carol Bradley Bursack, “and true mothering can be provided by anyone—a birth mother, an adoptive mother, a stepmother, a grandmother, an aunt, even a father.” Whether or not we realize it, we depend on all types of mothers for the well-being and safety of everyone. That includes babysitters, aunties, teachers, mentors, foster parents, godparents, neighbors, and so many others who contribute to the mothering of other people’s children.

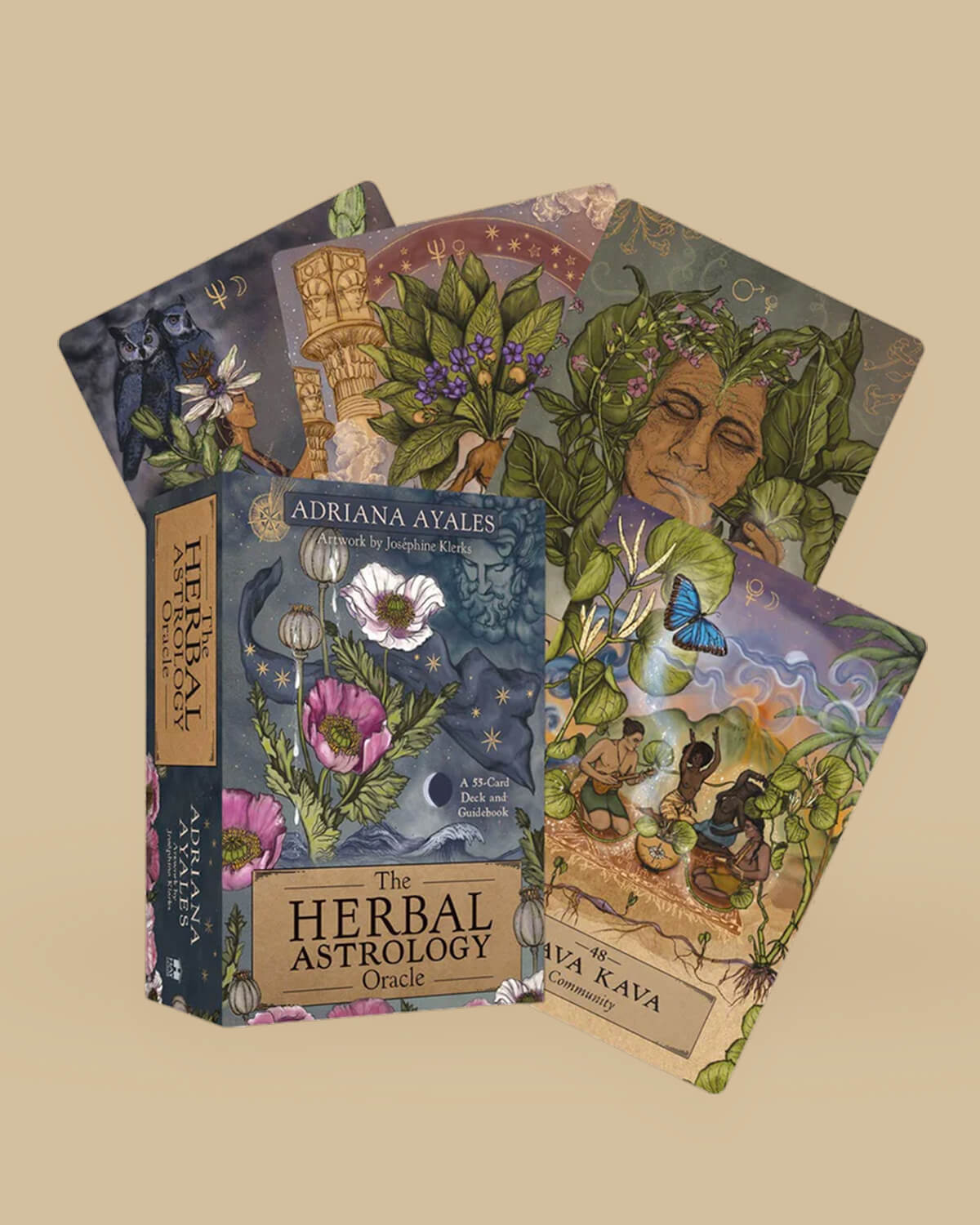

As the Undefining Motherhood founder Katy Huie Harrison, PhD, puts it, “Motherhood is not a definition. It’s a feeling,” adding, “I became a mother when I felt like one” to emphasize that anyone can be a mother, whenever and however they choose to be one. Our elders, our youth, and the most vulnerable among us are all shielded from harm and encouraged to thrive by these extraordinary caretakers. To bolster your mothering work and the work of mothers you love, our herbalists have also compiled a list of supportive plants that may benefit all types of mothers, however they may have come into this identity.

As Mother’s Day approaches, we want to offer all mothers our gratitude and some special gift options (to read more about our 2023 Mother’s Day Gift Guide and access our holiday sale, keep reading here).